Jewish History Timeline: A Comprehensive Overview

Exploring Jewish heritage, from ancient origins to modern Israel, this timeline details pivotal events—a rich narrative spanning millennia, documented in various sources.

Ancient Origins & Biblical Period (Pre-586 BCE)

This foundational era begins with God’s creation and the emergence of Abraham, recognized for his covenant with God—a pivotal moment establishing the Israelites’ unique relationship. The lineage continues through Isaac and Jacob (Israel), solidifying their ancestral ties.

A significant shift occurs with Joseph’s journey to Egypt, leading to the Israelites’ sojourn and eventual enslavement. The narrative then dramatically unfolds with Moses, receiving the Ten Commandments and leading the Exodus—a liberation marking the birth of Jewish law and identity.

Following liberation, the Israelites conquer Canaan and enter a period governed by Judges, characterized by cycles of obedience, disobedience, and deliverance, setting the stage for a unified kingdom.

The Patriarchal Age

This formative period centers on Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, establishing foundational beliefs and the covenant—the core of Jewish identity and destiny.

Abraham and the Covenant

Abraham’s story marks a pivotal shift in Jewish history, initiating a unique relationship with the Divine. God’s call to Abraham, recounted in Genesis, demanded leaving his homeland and forging a new nation. Central to this narrative is the covenant—a binding agreement promising land, descendants, and blessing in exchange for unwavering faith and obedience.

This covenant wasn’t merely a promise; it was a reciprocal commitment shaping Jewish identity. Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac, though ultimately averted, demonstrated profound devotion. This foundational narrative established monotheism and the concept of a chosen people, destined to be a “light unto the nations,” influencing Jewish thought and practice for millennia. The covenant remains a cornerstone of Jewish belief, emphasizing responsibility and a continuous dialogue with God.

Isaac and Jacob: Continuing the Lineage

Following Abraham, Isaac inherited the covenant, reaffirming the divine promise despite challenges. His life, though less dramatically recounted, solidified the lineage and demonstrated continued faith. Jacob, later renamed Israel, wrestled with both God and his brother Esau, securing his place as the patriarch of the twelve tribes.

Jacob’s journey, marked by deception and reconciliation, established the foundations of the Israelite nation. His twelve sons became the progenitors of the tribes, each contributing to the collective identity. Through their struggles and triumphs, the covenant was preserved and expanded, laying the groundwork for the Israelites’ eventual emergence as a people. These patriarchal narratives emphasize family, inheritance, and the enduring power of divine promise.

Joseph in Egypt & The Israelites’ Sojourn

Sold into slavery by his jealous brothers, Joseph rose to prominence in Egypt through his ability to interpret dreams. He skillfully navigated Egyptian society, eventually becoming a high-ranking official and saving the nation from famine. This pivotal role allowed him to invite his family – Jacob and the twelve tribes – to settle in the land of Goshen.

The Israelites’ sojourn in Egypt marked a period of growth and prosperity, yet also foreshadowed future hardship. Initially welcomed, they eventually faced oppression and enslavement under a new Pharaoh. This period of subjugation, lasting for generations, became a defining chapter in their history, setting the stage for the Exodus and their eventual liberation.

The Exodus and Wilderness Wanderings

Escaping Egyptian bondage, led by Moses, the Israelites experienced divine intervention and received the Ten Commandments, enduring forty years of desert trials.

Moses and the Ten Commandments

The pivotal figure of Moses, divinely appointed, led the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt, a foundational event in Jewish history. His ascent to Mount Sinai marked a transformative moment, where he received the Ten Commandments directly from God. These commandments, inscribed on stone tablets, established a moral and ethical framework for the Israelite nation, forming the basis of Jewish law and principles.

These foundational laws encompassed monotheism, prohibiting idolatry, and outlining principles of respect for parents, the sanctity of life, and honesty. The Ten Commandments weren’t merely rules, but a covenant—a binding agreement between God and the Israelites, establishing a unique relationship based on obedience and divine favor. This event solidified the Israelites’ identity as a nation chosen by God, dedicated to upholding His laws and principles.

The Conquest of Canaan

Following Moses’ death, Joshua led the Israelites in the challenging conquest of Canaan, the Promised Land. This period, marked by fierce battles and divine intervention, saw the Israelites overcome numerous Canaanite cities and tribes. The conquest wasn’t a swift, unified victory, but a protracted struggle spanning generations, involving tribal alliances and internal conflicts.

The division of the land among the twelve tribes formed the basis of Israelite settlement and identity. Significant sites like Jericho and Ai became symbolic of both the challenges and triumphs of this era. While the biblical narrative portrays a complete conquest, archaeological evidence suggests a more complex process of gradual infiltration and co-existence alongside the existing Canaanite population, shaping the cultural landscape of the region.

The Period of the Judges

After Joshua’s death, Israel entered a turbulent era governed by Judges – charismatic military and spiritual leaders raised by God to deliver the Israelites from oppression. This period, spanning roughly two centuries, was characterized by a cyclical pattern: apostasy, oppression by neighboring nations (like the Philistines, Moabites, and Midianites), repentance, and deliverance by a Judge.

Notable Judges include Deborah, Gideon, Samson, and Samuel, each embodying unique strengths and facing distinct challenges. The Book of Judges reveals a decentralized society struggling to maintain its identity and faithfulness. This era highlights a lack of central authority and a constant need for divine intervention, foreshadowing the desire for a unified monarchy to provide stability and leadership.

The United Monarchy

Israel’s transition to a kingdom under Saul, David, and Solomon marked an era of political unity, military strength, and the construction of the First Temple.

Saul, David, and Solomon

The reign of Saul initiated the monarchy, facing challenges from the Philistines and internal strife, ultimately leading to his tragic end. David, succeeding Saul, consolidated power, establishing Jerusalem as the political and religious center, and expanding Israel’s territory through military campaigns. His lineage was promised a lasting dynasty by God.

Solomon, David’s son, ushered in an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity, renowned for his wisdom and the magnificent First Temple in Jerusalem—a central hub for Jewish worship. However, his later years were marked by idolatry and heavy taxation, sowing seeds of discontent that contributed to the kingdom’s eventual division. These three kings represent a pivotal period in Jewish history, shaping its religious and political identity.

The First Temple in Jerusalem

Commissioned by King Solomon, the First Temple stood as the central sanctuary for Jewish worship for nearly four centuries, embodying God’s presence among His people. Constructed with immense wealth and skilled craftsmanship, it housed the Ark of the Covenant, containing the Ten Commandments—symbols of the covenant between God and Israel.

The Temple served as a focal point for pilgrimage festivals, sacrificial offerings, and priestly service, solidifying Jerusalem’s status as the holy city. Its eventual destruction by the Babylonians in 586 BCE marked a traumatic turning point in Jewish history, leading to the Babylonian exile and a profound spiritual crisis. The Temple’s legacy continues to resonate deeply within Jewish tradition.

The Divided Kingdom (930-586 BCE)

Following Solomon’s death, the kingdom fractured into Israel and Judah, marked by internal strife, prophetic warnings, and ultimately, the Babylonian exile’s devastation.

Israel and Judah

The split following Solomon’s reign created two distinct kingdoms: Israel in the north, comprising ten tribes, and Judah in the south, with Benjamin and Levi. Israel, initially stronger, succumbed to Assyrian conquest in 722 BCE, leading to the “Lost Tribes” dispersal. Judah, though smaller, endured for over a century longer, centered around Jerusalem and its Temple.

Political instability and religious divergence characterized both kingdoms. Jeroboam I established alternative worship sites in Israel, diverging from the Temple in Jerusalem. Judah, while maintaining the Davidic dynasty, faced periods of righteous and wicked kings. Throughout this era, prophets like Elijah and Isaiah emerged, delivering divine messages and warnings against idolatry and social injustice, foreshadowing impending doom.

Prophets and Warnings

Throughout the divided kingdom period, prophets played a crucial role, acting as divine messengers delivering stern warnings to both Israel and Judah. Figures like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel passionately denounced idolatry, social injustice, and empty ritualism, predicting devastating consequences if repentance didn’t occur. Their messages weren’t merely foretelling doom; they urged a return to the covenant with God, emphasizing ethical monotheism and righteous living.

These prophetic voices challenged royal authority and societal norms, often facing persecution for their unwavering commitment to truth. They offered glimpses of future restoration and messianic hope, promising a renewed covenant and a righteous kingdom, even amidst impending exile. Their writings became foundational texts within Jewish scripture.

The Babylonian Exile

Following the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE, the elite of Judah were exiled to Babylon, marking a traumatic turning point in Jewish history. This period, lasting approximately 50 years, witnessed the disruption of Jewish religious and political life, yet paradoxically fostered a strengthening of Jewish identity. Removed from their land and Temple, Jews established communities and maintained their traditions.

During exile, the Hebrew Bible began to take its final form, and synagogues emerged as centers of worship and study. The experience profoundly shaped Jewish theology, emphasizing the importance of law, prayer, and the hope for eventual return and rebuilding—a foundational element of Jewish faith.

Second Temple Period (539 BCE – 70 CE)

This era saw the return from Babylonian exile, Temple rebuilding, Hellenistic influences, the Maccabean revolt, and ultimately, Roman dominion over Judea.

Return from Exile & Rebuilding the Temple

Following the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great issued a decree permitting the exiled Jews to return to Judah and rebuild their Temple. This marked a pivotal moment, initiating the Second Temple Period. Led by figures like Zerubbabel, the first group returned, facing challenges from surrounding populations who offered to assist in rebuilding, but were refused.

Construction of the Second Temple commenced around 535 BCE and was completed in 516 BCE, a significantly less opulent structure than Solomon’s First Temple. This rebuilding wasn’t merely a physical act; it symbolized the restoration of Jewish religious life and identity after decades of displacement. The period also witnessed the work of prophets like Haggai and Zechariah, encouraging the people and emphasizing the importance of rebuilding the Temple as a spiritual endeavor.

Hellenistic Influence & The Maccabean Revolt

Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BCE brought Hellenistic culture to Judea, initiating a period of significant cultural exchange and, eventually, conflict. While some Jews embraced Hellenization, adopting Greek customs and language, others staunchly resisted, viewing it as a threat to their religious traditions and identity. This tension escalated under Antiochus IV Epiphanes, a Seleucid king who actively sought to impose Hellenistic practices, even desecrating the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

This sacrilege sparked the Maccabean Revolt (167-160 BCE), led by the Hasmonean family. Judah Maccabee and his brothers successfully fought against the Seleucid Empire, reclaiming the Temple and rededicating it to Jewish worship – an event commemorated by Hanukkah. The revolt ultimately led to the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom, the Hasmonean dynasty, lasting for over a century.

Roman Rule & Jewish Sects (Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes)

Roman control over Judea began in 63 BCE, initially through client kings but gradually evolving into direct provincial rule. This period witnessed the rise of distinct Jewish sects, each interpreting Jewish law and tradition differently. The Pharisees, emphasizing oral law and future life, gained widespread popular support. The Sadducees, associated with the priestly aristocracy, focused on the written Torah and rejected resurrection.

The Essenes, a more ascetic group, withdrew from society, possibly responsible for the Dead Sea Scrolls. These differing ideologies fueled internal tensions and contributed to periodic uprisings against Roman authority. The complex interplay between Roman governance and Jewish religious and political factions set the stage for future conflicts and ultimately, the destruction of the Second Temple.

The Rise of Christianity & Jewish-Roman Wars

Early Christianity emerged within a Jewish context, but growing tensions and multiple revolts against Roman rule culminated in devastating wars and upheaval.

Early Christian-Jewish Relations

Initially, Christianity arose as a sect within Judaism, with early followers identifying as Jewish and observing Jewish laws and customs. Jesus and his disciples were Jewish, and the earliest Christian communities worshipped in synagogues. However, differing interpretations of Jewish law and the messianic role of Jesus led to increasing separation.

Paul of Tarsus played a crucial role in spreading Christianity among Gentiles (non-Jews), lessening the emphasis on strict adherence to Jewish law for converts. This divergence created theological and social friction, contributing to a growing rift between the two groups. As Christianity gained momentum, it began to distance itself from its Jewish roots, eventually establishing itself as a distinct religion.

Historical accounts reveal periods of both cooperation and conflict, with accusations and misunderstandings fueling animosity. This complex relationship laid the groundwork for future interactions and, unfortunately, periods of persecution.

The Destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE)

The First Jewish-Roman War culminated in the siege and destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE by Roman forces under Titus. This catastrophic event marked a pivotal turning point in Jewish history, ending the era of Temple worship and sacrificial rituals central to Jewish religious life.

The Temple’s destruction led to widespread devastation and loss of life, forcing many Jews into exile and scattering them throughout the Roman Empire. It fundamentally altered Jewish religious practice, shifting the focus from Temple-based worship to synagogue-based prayer and study of the Torah.

This event profoundly impacted Jewish identity and communal structure, initiating a period of significant theological and cultural adaptation. The loss of the Temple became a symbol of national tragedy and a central theme in Jewish mourning and remembrance.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-135 CE)

Following decades of Roman oppression, the Bar Kokhba Revolt erupted in 132 CE, led by Simon bar Kokhba, who was hailed by some as a messianic figure. This widespread uprising aimed to regain Jewish independence and rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, challenging Roman authority in Judea.

The revolt initially achieved considerable success, establishing a short-lived independent Jewish state. However, the Romans, under Emperor Hadrian, responded with overwhelming military force, ultimately suppressing the rebellion after three years of fierce fighting.

The revolt’s failure had devastating consequences for the Jewish population, resulting in massacres, enslavement, and further exile. Judea was transformed into Syria Palaestina, and Jewish religious practice was severely restricted, marking a dark chapter in Jewish history.

Diaspora & Medieval Period (70 CE – 1500 CE)

Post-Temple destruction, Jewish communities flourished across Babylonia, Islamic Spain, and Europe, facing both challenges and remarkable cultural achievements.

Jewish Life in Babylonia

Following the Babylonian Exile in 586 BCE, a significant Jewish community established itself in Babylonia, persisting for centuries and profoundly shaping Jewish identity. Unlike communities elsewhere, Babylonian Jews enjoyed periods of relative autonomy and prosperity, fostering a unique cultural and intellectual environment.

The Babylonian Talmud, compiled by scholars in Babylonia, became a cornerstone of Jewish law and thought, influencing Jewish practice worldwide. This period witnessed the rise of prominent rabbinic academies, centers of learning that preserved and expanded Jewish knowledge. Jewish life wasn’t without challenges, facing occasional persecution, but the community demonstrated remarkable resilience, maintaining its traditions and contributing significantly to the broader Mesopotamian society.

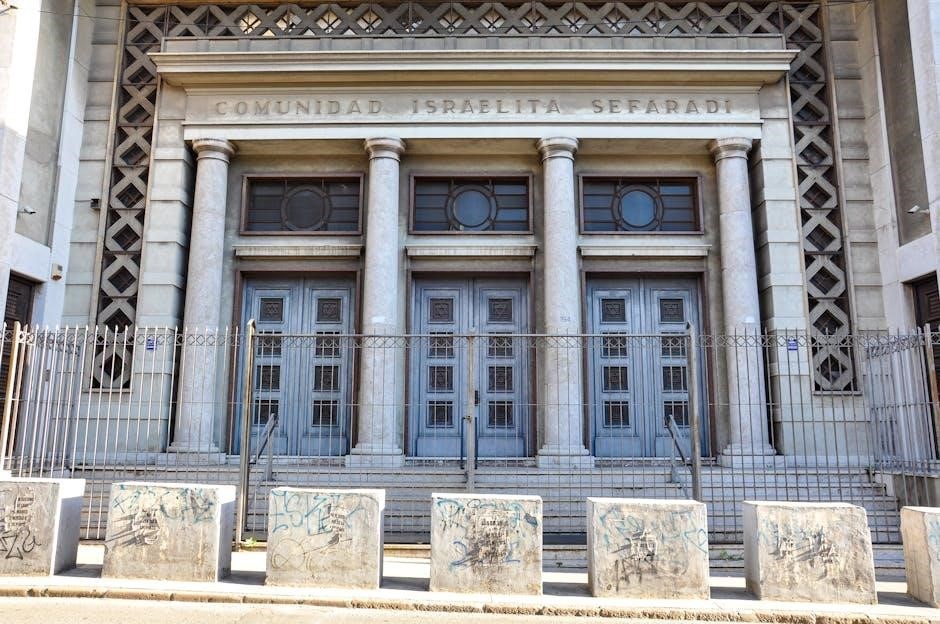

Jewish Communities in Islamic Spain (Al-Andalus)

During the period of Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), Jewish communities flourished for several centuries, experiencing a “Golden Age” of cultural and intellectual achievement. Under Muslim rule, Jews often enjoyed greater religious tolerance and economic opportunities compared to other parts of Europe, contributing significantly to Spanish society.

Jewish scholars excelled in fields like medicine, astronomy, poetry, and philosophy, often collaborating with their Muslim counterparts. Figures like Maimonides, a renowned philosopher and physician, emerged from this era. However, this period wasn’t consistently peaceful; fluctuations in political climate sometimes led to periods of persecution, ultimately culminating in the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492.

Jewish Life in Medieval Europe: Challenges & Achievements

Medieval Europe presented a complex landscape for Jewish communities, marked by both significant achievements and persistent challenges. Often confined to specific occupations like trade and moneylending due to restrictions imposed by Christian authorities, Jews faced discrimination, accusations, and periodic expulsions.

Despite these hardships, Jewish life thrived in many areas. Jewish scholars preserved and developed religious texts, while communities established synagogues and maintained distinct cultural identities. Kabbalah, a mystical Jewish tradition, gained prominence during this period. Simultaneously, Jews navigated legal limitations and social prejudice, often relying on communal self-governance to maintain stability.

The Holocaust (1933-1945)

A horrific genocide, the Holocaust systematically murdered six million Jews across Europe, a deeply documented tragedy fueled by Nazi ideology and antisemitism.

Rise of Nazism and Anti-Semitism

The seeds of the Holocaust were sown in the post-World War I environment, with widespread economic hardship and political instability in Germany. This fertile ground allowed extremist ideologies, particularly Nazism, to flourish. Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party rose to power in 1933, promoting a virulent strain of antisemitism that blamed Jews for Germany’s problems.

Nazi ideology portrayed Jews as an inferior race, a threat to German racial purity, and enemies of the state. This propaganda, disseminated through various media, fueled hatred and discrimination. Early Nazi policies involved boycotts of Jewish businesses, the dismissal of Jewish civil servants, and the enactment of discriminatory laws like the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, stripping Jews of their citizenship and rights. These escalating measures created an atmosphere of fear and persecution, laying the foundation for the horrors to come.

Ghettos and Concentration Camps

As persecution intensified, the Nazis implemented policies of forced segregation and confinement. Beginning in 1939, Jews were systematically herded into overcrowded, unsanitary ghettos in cities across Nazi-occupied Europe, like Warsaw and Lodz. These ghettos were sealed off, isolating Jewish communities and subjecting them to starvation, disease, and brutality.

Simultaneously, the Nazis established a network of concentration camps, initially intended for political prisoners, but soon used to imprison and exploit Jews. These camps, such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, and Sobibor, became sites of systematic murder. Jews were subjected to forced labor, medical experiments, and ultimately, mass extermination in gas chambers. The conditions within these camps were horrific, resulting in unimaginable suffering and death.

The Six Million: Remembering the Victims

The Holocaust represents the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators. This genocide extinguished entire families, communities, and a vibrant cultural heritage. Each victim possessed a unique identity, dreams, and potential, tragically lost to hatred and intolerance.

Remembering the six million is not merely a historical obligation, but a moral imperative. Through testimonies, memorials, and education, we strive to honor their memory and ensure that such atrocities never happen again. Preserving their stories combats denial, challenges prejudice, and promotes understanding. It’s a solemn duty to learn from the past and build a future founded on respect and compassion.

Modern Era & The State of Israel (1945 – Present)

Post-Holocaust, the establishment of Israel in 1948 marked a turning point, facing ongoing conflicts while fostering vibrant Jewish life and innovation.

Post-Holocaust Displacement & The DP Camps

Following World War II, hundreds of thousands of Jewish survivors found themselves displaced, lacking homes and families, facing immense trauma. Allied forces established Displaced Persons (DP) camps across Europe, initially intended as temporary shelters. These camps, however, became crucial hubs for rebuilding Jewish lives and fostering a renewed sense of community.

Within the DP camps, survivors sought to piece together shattered identities, locate lost relatives, and grapple with the horrors they had endured. Jewish organizations played a vital role in providing aid, education, and psychological support. Simultaneously, a powerful movement for establishing a Jewish state in Palestine gained momentum within the camps, fueled by the desire for self-determination and a safe haven. The DP camps ultimately served as a critical stepping stone for many Jewish refugees on their journey to Israel.

The Founding of the State of Israel (1948)

On May 14, 1948, amidst international turmoil and escalating conflict, David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel. This historic declaration followed the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, aiming to create separate Jewish and Arab states. However, the plan was rejected by Arab leaders, leading to the outbreak of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

The newly formed nation faced immediate challenges, battling for its survival against neighboring Arab armies. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, Israel persevered, securing its independence through fierce determination and strategic military action. The war resulted in significant displacement of Palestinian Arabs and further shaped the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. The founding of Israel marked a pivotal moment in Jewish history, fulfilling a centuries-old dream of self-determination.

The Six-Day War & Subsequent Conflicts

In June 1967, escalating tensions with neighboring Arab states culminated in the Six-Day War. Preemptively striking against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, Israel achieved a swift and decisive victory, capturing the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, and Golan Heights. This dramatically altered the map of the region and initiated a prolonged period of Israeli military occupation.

Following the Six-Day War, numerous conflicts ensued, including the Yom Kippur War in 1973, a surprise attack by Egypt and Syria. Subsequent conflicts, like the Lebanon Wars and ongoing clashes with Palestinian militant groups, continued to shape Israeli-Arab relations. These conflicts underscored the complex and enduring challenges to peace in the region, impacting both Israelis and Palestinians for decades.

Contemporary Jewish Life & Challenges

Today, Jewish communities thrive globally, yet face evolving challenges. Rising antisemitism, manifesting in hate crimes and online harassment, remains a significant concern worldwide. Maintaining Jewish identity amidst assimilation and intermarriage presents ongoing discussions within communities. The State of Israel continues to be a central focus, sparking debate regarding its security, policies, and role in the diaspora.

Furthermore, internal divisions regarding religious practice and political views contribute to complex dynamics. Supporting vulnerable populations, preserving Jewish heritage, and fostering interfaith dialogue are crucial priorities. Navigating these multifaceted issues ensures the continuity and vibrancy of Jewish life for future generations, adapting to a changing world.